This is an existentialist story about a man who learns he has stomach cancer, leading to his reconsidering of life, which he realizes has been utterly wasted up until this point.

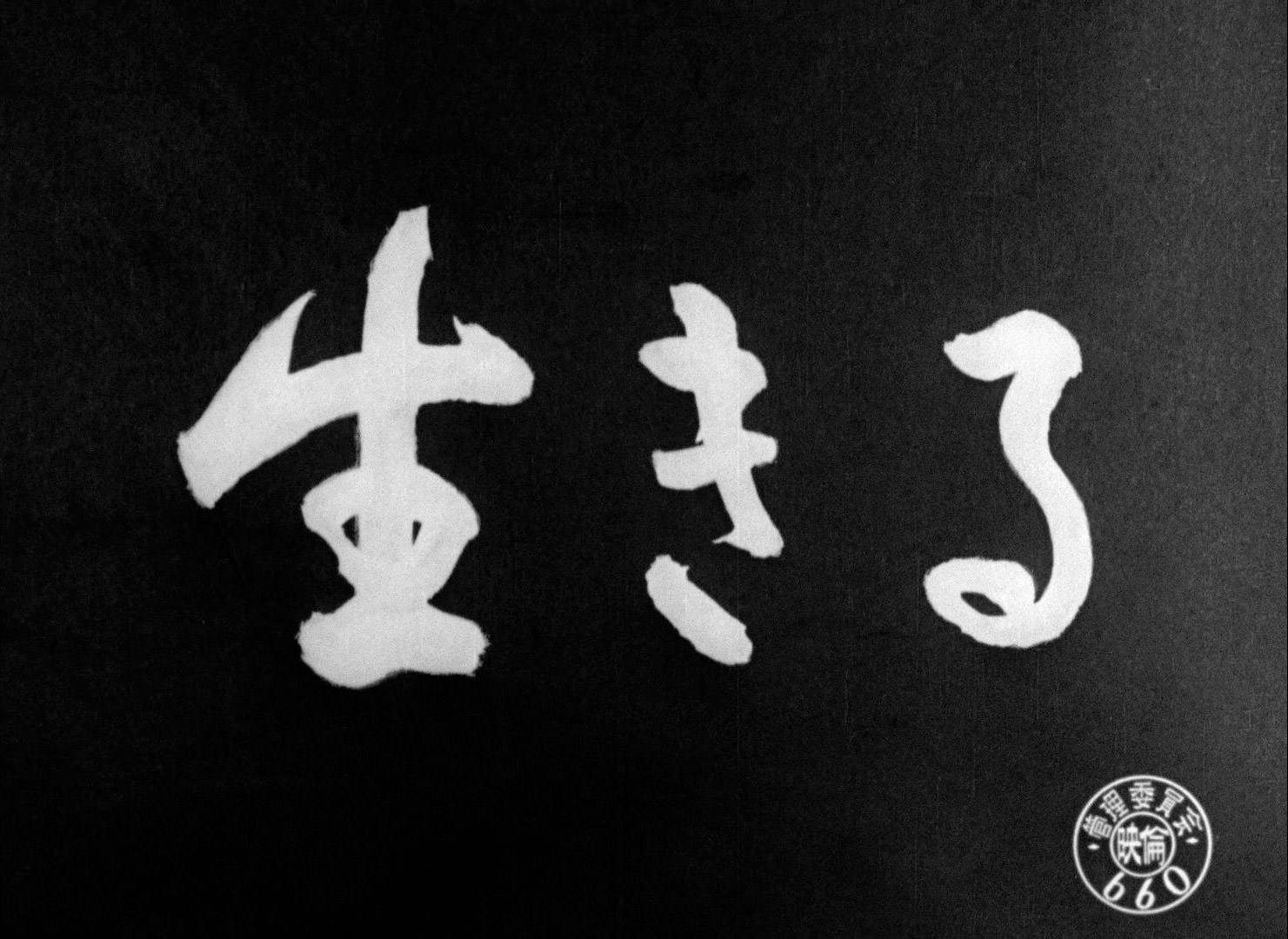

As it turns out, he realizes he hasn’t really been living at all. What’s inadvertently happened is that his job has turned into his life - the job of being section chief at one of the endless wasteful government bureaucracies. From the point of his diagnosis, his challenge is trying, in the brief life he has left, to figure out what it means to actually live. Thus the name of the film in English: TO LIVE.

This is a sad and deeply disturbing film, not disturbing in the explicit sense of a horror or a war movie, but disturbing because these are the horrors of everyday life. It is too real: the horror of mundane office life, of government bureaucracy, of the disconnect between life and work, of a cancer slowly eating away at remaining life, of life’s clock itself ticking down, chiming each hour closer to death. The horror of growing old and losing vitality and life’s energy.

In the very opening of the film, a group of women is petitioning a government agency to turn a cesspool into a children’s park and playground. In typical government fashion, the responsibility is pushed from department to department, with no one department wanting to take responsibility. Thus the park becomes a pretty clearly established MacGuffin.

The protagonist - Kenji Watanabe - has been diagnosed with stomach cancer, but is initially alone in his discomfort, with no one close or trusting enough to help him. Even the doctors themselves are distrustful, as they don’t directly tell him his diagnosis - Watanabe has to find out indirectly. After his diagnosis he walks outside of the hospital and we get the sense that he no longer belongs in the world - the busy street with with cars speeding by is in a sense life itself passing by - something that is now very alien.

It’s a world in which he no longer belongs.

He’s an outcast at work, the boring boss figurehead who’s probably in his position based on seniority alone. He’s also an outcast at home, where his wife died many years ago, and where he now lives with his ungrateful and highly dislikable son and his son’s girlfriend. He reflects on his life which was devoted to his son, and wants to break the news of his cancer to him. He looks for various ways to tell him. But the son has turned his back on him and effectively blocks him out.

There’s no one close enough for Watanabe to break the news to. The first person he tells is a complete stranger at a bar, an apparently alcoholic struggling writer. Watanabe eventually confesses that he wants to learn how to live life, and asks the writer to help him spend his money all at once, while he still has time. The writer refuses his money and instead offers to pay with his own money, which immediately makes him the first character Watanabe can trust. They go out and visit all the vices of nightlife in the city: booze, clubs, loud bars, crowded dance halls, stripteases.

They find themselves at a club with a piano player playing a boogie-woogie tune which people are energetically dancing to. People dancing, full of life.

Watanabe requests an old song which gives away his age: the hit of 1915, Gondola no Uta (ゴンドラの唄, “The Gondola Song”). People try to dance to it, but he sings in such a depressing way that is a downer for everyone there. The camera pulls back from the face of the writer, whose thin and pale face is baring his lower teeth, and his whole appearing perhaps not coincidentally resembling a skeleton, utterly in shock.

The night ends with a taxiride home with some revolting and annoying prostitutes. Watanabe has to get the taxi to stop so he can vomit on the sidewalk. It’s the reminder of his stomach ulcer, a problem that cannot be drunk away.

But it turns out these places aren’t what Watanabe is looking for. The day after, he roams the streets continuing to look, and by chance runs into a young girl from work. A girl that is still very full of life, as revealed by her innocent full smile. A girl that doesn’t belong at Watanabe’s workplace, and is consequently quitting.

Back home, the son has blocked him out with his newspaper, and the son’s girlfriend with her knitting and furtive glances. They are so resistant and are unable to listen. They think he’s having a relationship with the young girl from the office, and accuse without even listening to Watanabe.

Watanabe meets with the girl one last time, and finally confesses that he has cancer and not long to live, and that his life has been a waste. He confesses that the girl brings out some life still remaining in him.

The girl is now working at a factory making toy bunnies, and she explains how she feels as if by making the toys she’s reaching out to all the children across the Japan. She has found a workplace where she belongs. She has found meaning in her work.

“Why don’t you try making something too?” she says.

And then his haunting reply: “It’s too late.”

But soon after he appears to have a realization. He leaves the girl and walks straight out of the restaurant, with a clear and definitely purpose. It’s the last we see of the girl - she’s served her purpose in showing him the way. “Happy birthday to you” is playing for a young girl as Watanabe is exiting the scene, but it’s really his birthday, or rather his rebirth.

“Happy birthday to you” plays again as Watanabe goes out to personally inspect the future park site - this becomes his life goal. The challenge that no government agency wanted to take on.

Then the scene cuts to five months later. Suddenly Watanabe is dead.

This is the climax of the film, which happens at a somewhat unusual place. The rest of the story is told through his funeral and flashbacks. This is really my only complaint with the movie - we have to spend the rest of the movie in a room with people we’ve grown to dislike and distrust. Coworkers, bureaucrats, and the uncaring son and girlfriend. The bureaucrats continue bureaucrating, and try to take credit for building Watanabe’s park, an effort they all quickly turned down at the beginning of the film.

Then very briefly, some people we trust and care about: the group of women originally petitioning for the park arrive and mourn very intently at Watanabe’s altar, an act of sincerity which inadvertently shames the insincere bickering bureaucrats.

Then we return to the room of people we dislike, and we are forced to spend more time with these unlikeable characters. Because of this I think this part just drags on much longer than needed, and slows down the pacing of the film. But then there is some redemption: some of the bureaucrats finally acknowledge Watanabe’s efforts, and they appear to be themselves inspired and changed.

We also get flashbacks of Watanabe stubbornly running up against challenge after challenge to get the park built, even in the face of gangsters, presumably the Yakuza, who showed him leniency. I think this is worth showing briefly, but it’s already been strongly established that this government is a very inefficient and resistant to change, so much of this seems like unnecessary storyline that makes the film drag.

However, all this waiting and slow pacing leads to a worthwhile payoff: the policeman stopping by the funeral to return Watanabe’s hat and pay his respects. He’s the one that recounts the very beautiful scene with Watanabe singing his Gondola Song on a swing in his new park, amidst falling fresh snow. That’s the last we see of Watanabe alive, and how truly alive and happy he was.

The film ends with a strong hint that some coworkers’ attitudes and behaviors have now been changed by Watanabe, and that his efforts have affected more change than just the children’s playground. His actions have really lead to a greater good in the world.

This has become one of my favorite films, for the very reason that it’s a challenge to how we should live. This is how art and how films can improve our lives and make us better people - they involve us in a world and let us learn from the characters in that world. And from this film is the challenge calling out clearly: live your life, create, don’t waste your life, do good through your work.

Comments